(category)Foundations

On Market Timing: What if you were the luckiest investor in India?On Market Timing: What if you were the luckiest investor in India?

Covid, lockdowns, forced working from home were the guests who would never leave. After two years, we had just about managed to manoeuvre them toward the door. And just as you cracked the door open with the pleasurable anticipation of their exit, this other group of distant and not very likeable relatives in the form of Russia-Ukraine, barges in, arguing loudly among themselves. The markets have more than doubled from the low of March 2020, up almost 130% as of writing this. They're also up 40% from pre-March2020-crash levels, so even the Feb 2020 investor has done pretty well. But no one wants to be that guy. The guy who invested just before a big fall. And so, once more the most frequent question is: Is this a good time to invest? In other words, how do I NOT be the shmuck who bought at the top?

Anoop Vijaykumar•

The markets have more than doubled from the low of March 2020, up almost 130% as of writing this. They're also up 40% from pre-March2020-crash levels, so even the Feb 2020 investor has done pretty well. But no one wants to be that guy. The guy who invested just before a big fall.

And so, once more the most frequent question is: Is this a good time to invest? In other words, how do I NOT be the shmuck who bought at the top?

Two years ago, markets fell, a lot. Worse falls had happened in the past, but this one stood out for two reasons.

It had been a while: We had not seen falls worse than 30% since the Great Financial Crisis meltdown, but that was over a decade ago.

The sheer ferocity of the fall: past crashes had played out over "reasonable" periods of a year or longer. The dot-com collapse took three years to play out. In comparison, the March 2020 fall took all of 1 month, most of the falling took just three weeks.

Someone getting a chunk of cash and investing a lump sum into markets in the first couple weeks of Feb 2020 would have been buying the NIFTY at about 12,200. Imagine, if the process of getting the money was delayed by just two-three weeks, courtesy, maybe a PSU Bank Branch manager slowing the process down because he needed notarised attested copies of various documents in triplicate before agreeing to hand over the cheque. You'd be buying almost 40% more units with the same money.

The bureaucrat would be the surprise recipient of a box of sweets every Diwali for the rest of his life.

Covid, lockdowns, forced working from home were the guests who would never leave. And after two years, we'd just about managed to deftly manoeuvre them toward the door. And just as you cracked the door open with the pleasurable anticipation of their exit, this other group of distant and not very likeable relatives in the form of Russia-Ukraine, barges in, arguing loudly among themselves.

The markets have more than doubled from the low of March 2020, up almost 130% as of writing this. They're also up 40% from pre-March2020-crash levels, so even the Feb 2020 investor has done pretty well. But no one wants to be that guy. The guy who invested just before a big fall.

And so, once more the most frequent question is: Is this a good time to invest? In other words, how do I not be the shmuck who bought at the top?

What if you are the world's dumbest unluckiest investor?

Chart shows the Nifty in 2008 and when a lucky and an unlucky investor would invest in the year.

In 2008, Unlucky Umang would have deployed his annual SIP on 8th Jan with the Nifty at 6,250. Lucky Lokesh would have deployed his at 3.15pm on 27th Oct, at about 2,520, heck maybe even at 2,248. By the end of the year, Umang's investment that year would have lost over half its value. Lokesh would incredibly, be up 18%.

Now imagine, the respective charts for every year from 1990 to 2022 with Lucky Lokesh always finding the bottom when adding his SIP, Unlucky Umang, the top. Remember, each year, they add new money on the respective best, worst dates.

Here's a question: After three decades from 1990 to 2022, what is Lucky Lokesh's annualised portfolio outperformance over Unlucky Umang?

🔘 > 500bps

🔘 300 - 400 bps

🔘 200 - 300 bps

🔘 < 200 bps

Now consider Regular Reema, who puts in her money at the start of the year and moves on to things more productive than worrying about what the market will do. What is Lucky Lokesh's annualised portfolio outperformance over Regular Reema?

🔘 > 500bps

🔘 300 - 400 bps

🔘 200 - 300 bps

🔘 < 200 bps

Over 31 years: 213 bps (13.3% minus 11.2%), the difference between buying at the bottom over buying at the top, every. single. year.

74 bps, the difference between buying at the bottom and just buying on a given day of the year.

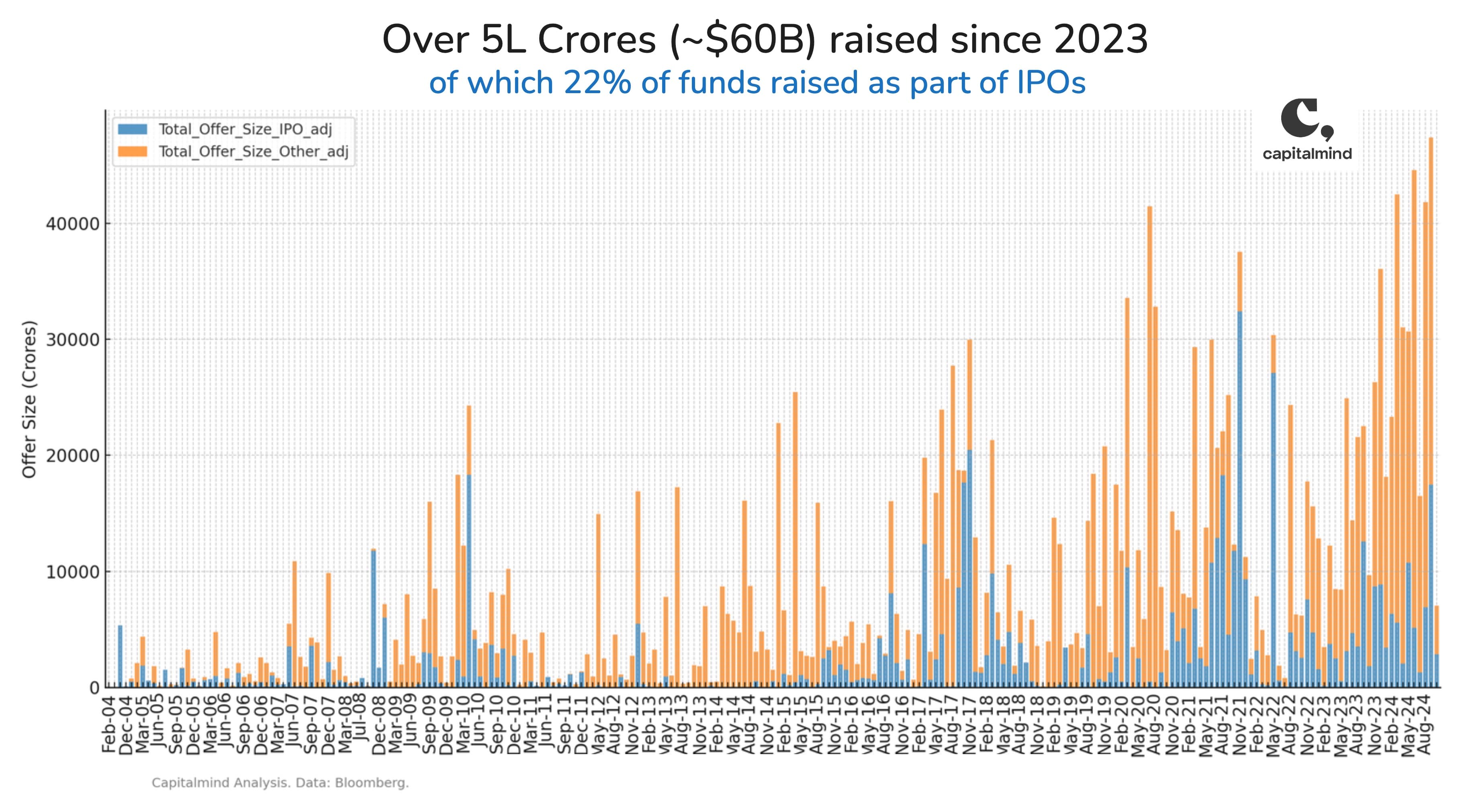

We analyzed what it would mean to have bought the Nifty top / bottom / one day in the year / every month starting at various points from 1990 / 2000 / 2005 / 2010 / 2015 until March 2022.

The chart below assumes annual SIPs of ₹10k. The Monthly SIP scenario assumes ₹1k.

Chart compares annualised returns for the three with different start years until Mar 2022.

If you had the distinction of diligently investing an equal amount annually, and finding the top in each and every one of those years, your annualised return from 1990 to 2022 would be 11.2%. Your mirror image in this world, the investor who added money at the bottom every year: 13.3%. A difference of 213 basis points.

Even over shorter time frames, the unlucky investor still manages double-digit returns, outpacing inflation and fixed income returns. Remember, that's the worst case.

Given how scary we find the prospect of investing at the "wrong" time, you'd imagine the cumulative impact would be catastrophic. Turns out it's not.

The reason: Markets mostly go up. On a 1-year time frame, markets are up nearly 70% of the time. This means in any given rolling 1 year period, the market will be higher than where it started 70% of the time.

Also, with time, the significance of new money you add or choose not to add becomes insignificant as the accumulated returns form the bulk of your portfolio. i.e. the unintuitive magic of compounding.

There is one way to mess with your portfolio. Make discretionary full exit and re-entry decisions based on market predictions. Most of us kid ourselves when we say that of course, I'll exit when markets become euphoric and re-enter when pessimism is rife.

One good way to stay grounded as investors and investment managers and avoid hubris is to understand how, at some point, every legendary investor has had their backside handed to them.

And that's from the folks who've been exceptionally good at calling bubbles in the past.

For instance, this one is about Stanley Druckenmiller. For those who haven't heard the name, just take it that he's a hall-of-fame investment manager with the returns and track record to match. This, in his own words:

"I made a lot of mistakes, but I made one real doozy. So, this is kind of a funny story, at least it is 15 years later because the pain has subsided a little. But in 1999 after Yahoo and America Online had already gone up like tenfold, I got the bright idea at Soros to short internet stocks. And I put 200 million in them in about February and by mid-March the 200 million short I had, lost $600 million on, gotten completely beat up and was down like 15 percent on the year. And I was very proud of the fact that I never had a down year, and I thought well, I’m finished.

So, the next thing that happens is I can’t remember whether I went to Silicon Valley or I talked to some 22-year-old with Asperger’s. But whoever it was, they convinced me about this new tech boom that was going to take place. So I went and hired a couple of gunslingers because we only knew about IBM and Hewlett-Packard. I needed Veritas and Verisign. I wanted the six. So, we hired this guy and we end up on the year — we had been down 15 and we ended up like 35 percent on the year. And the Nasdaq’s gone up 400 percent.

So, I’ll never forget it. January of 2000 I go into Soros’s office and I say I’m selling all the tech stocks, selling everything. This is crazy…at 104 times earnings. This is nuts. Just kind of as I explained earlier, we’re going to step aside, wait for the next fat pitch. I didn’t fire the two gunslingers. They didn’t have enough money to really hurt the fund, but they started making 3 percent a day and I’m out. It is driving me nuts. I mean their little account is like up 50 percent on the year. I think Quantum was up seven. It’s just sitting there.

So like around March I could feel it coming. I just — I had to play. I couldn’t help myself. And three times the same week I pick up a — don’t do it. Don’t do it. Anyway, I pick up the phone finally. I think I missed the top by an hour. I bought $6 billion worth of tech stocks, and in six weeks I had left Soros and I had lost $3 billion in that one play. You asked me what I learned. I didn’t learn anything. I already knew that I wasn’t supposed to do that. I was just an emotional basket case and couldn’t help myself. So, maybe I learned not to do it again, but I already knew that." [reference]

Even the gun professionals get it wrong sometimes. What of us mortals?

Keep this in mind when seeking certainty about how the world will look a year from now. What the crisis means for markets. How supply disruptions in Oil, Wheat, Fertilisers, Sunflower oil, nickel will impact the global economy. How companies will pull back their global supply chains as a longer-term outcome, the end of globalisation.

I'd say leave all of that to the fund managers on financial media, with the burden of sounding like they've got it all figured out.

The list of folks who have successfully picked market tops consistently is a blank sheet of paper.

Instead, ask yourself, how bad does it get when you get the "Is it the right time to invest" answer wrong. Turns out, not so bad as long as you stay in the game.

An important caveat: While discretionary calls often fail spectacularly, simple non-discretionary rules to decide exit and re-entry have a place in an investor's toolkit. The opposite of a good idea can also be a good idea.

Suggested Reading:

Common-sense position sizing for investors

The five commonly held investing myths

How to think about picking stocks in India

Related Posts

Make your money work as hard as you do.

Talk to a Capitalmind Client AdvisorInvesting is not one size fits all

Learn more about our distinct investment strategies and how they fit into your portfolio.

Learn more about our portfoliosUnlock your wealth potential

Start your journey today